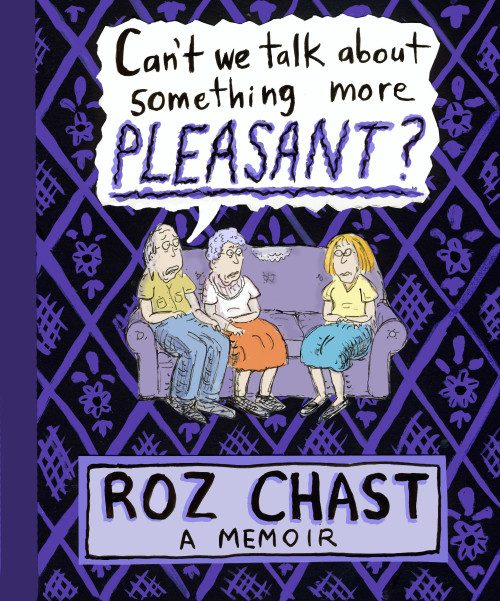

Many people might recognize Roz Chast’s cartoons from the New Yorker, where they have appeared since 1978. Personally, my first recollection of her work has to do with one of my favorite books from childhood, Now Everybody Really Hates Me, which she illustrated. In her memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Chast uses cartoons — something she is quite comfortable with — to illustrate the difficult topics of taking care of aging parents and talking to them about death and their final wishes when the time for the end comes near.

Many people might recognize Roz Chast’s cartoons from the New Yorker, where they have appeared since 1978. Personally, my first recollection of her work has to do with one of my favorite books from childhood, Now Everybody Really Hates Me, which she illustrated. In her memoir, Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Chast uses cartoons — something she is quite comfortable with — to illustrate the difficult topics of taking care of aging parents and talking to them about death and their final wishes when the time for the end comes near.

In Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Chast injects humorous examples and anecdotes into her drawings.

The majority of Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? reads like one large graphic novel filled with Chast’s clever cartoons and some of the author’s personal photos interspersed throughout from beginning to end. I thought that this method works best for trying to understand and navigate through these difficult topics that children must confront at some point with their aging parents.

In Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?, Chast injects humorous examples and anecdotes into her drawings. The humor helps the reader understand better about some of the major — and oft-baffling — medical and end-of-life terminology.

As Chast puts it, in addition to learning about the money her parents receive and pay, “we also did wills and filled out health-care proxy forms and power of attorney forms. It was all stuff I never wanted to know about, but that’s what an Elder Lawyer was for: to help you learn about it.”

One such example would be chapter 3 in the book, which talks about the meeting Chast set up for her parents and her to iron out the nitty-gritty details about all topics relevant to final wishes and death. As Chast puts it, in addition to learning about the money her parents receive and pay, “we also did wills and filled out health-care proxy forms and power of attorney forms. It was all stuff I never wanted to know about, but that’s what an Elder Lawyer was for: to help you learn about it.”

To further illustrate her point, Chast includes a little cartoon about what happened during their meeting with the elder lawyer and compares how challenging all of the personal questions and official documents to sign can be with how opinions about plastic surgery can change at different stages in one’s life, especially when looks start to fade the older we get.

As Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant? continues, Chast allows the reader very personal glimpses into her parents’ increasing frailty (both her mother’s series of falls and her father’s ever-increasing dementia) and how it gradually progresses into their not being able to live at the home they have shared for more than fifty years. She allows us to see the struggles she faced with getting them to move into an assisted care facility and how there were constant battles between child and parents about the extent of tasks they could still physically and mentally handle without any extra help.

Probably the most intimate details Chast shares, in both words and drawings, are the individual days her parents died — almost two years apart — and her unique relationships with each parent and how she coped and dealt with learning of their losses.

How Chast handles these moments serves as gentle reminders that we all must face these moments someday no matter how close or how strained our relationships with our parents might have been over the years.

“Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” A Memoir by Roz Chast

“Can’t We Talk About Something More Pleasant?” A Memoir by Roz Chast

Final Messages of the Dying

Final Messages of the Dying

Will I Die in Pain?

Will I Die in Pain?